The Back Door For Crypto Or The Front Door For Walmart?

By Ro Patel, Partner at Hack VC

Introduction

Crypto has a pervasive problem to which participants have grown numb. While largely ignored, the pressure continues to mount between three key parties: investors, founders, and regulators. The eventual solution will likely be a big bang in the evolution of crypto as an asset class. The problem to which I am referring is broadly labeled governance tokens. Specifically, many governance tokens fail to accrue value to holders and the “governance” moniker is merely a red herring in that it conveys value at all. The first step in solving any problem is recognizing its existence and defining its parameters. Now that we’ve done that, let’s get into it.

Back to Basics

Go back to the first time you were redpilled on Ethereum. Recall your initial thoughts in that moment when the concept first clicked. For me, it was simple and brilliant:

- Developers build an application that serves users

- They use these cool, new things called smart contracts, which allow logic to execute on a decentralized network of nodes run by miners/validators churning out blocks

- A fungible token is created, which represents ownership of the application

- Users pay fees, in some form, for said application

- Fees accrue to token holders for owning a share of the application

This line of thought is not unique, nor is it complicated. If anything, it’s tidy. And, most importantly: it just makes sense. Holding the above assumptions constant, a token is effectively a unit in a fee-generating platform.

In practice, however, the above structure is a lot messier. I know that the elephant in the room, which is largely responsible for this mess, is regulation. We will get to that later. For now, let me paint the true, sobering picture:

- Developers build an application that serves users

- They use these cool, new things called smart contracts, which allow logic to execute on a decentralized network of nodes run by miners/validators churning out blocks

- A fungible token is created, which represents ownership of the application

- Users pay fees, in some form, for said application

So far so good…

- Fees don’t accrue to tokenholders. Instead they accrue to any combination of:

Other users: think LP tokens on Uniswap, taker fees go to liquidity providers P2P1

- A Treasury or DAO where either (1) token holders vote on what to do with this treasury (a possible, albeit empirically rare, proposal might vote to issue the accrued fees to token holders, but, more commonly, proposals involve spending fees to improve and grow the protocol) or (2) the treasury balance sits largely idle and might grow passively over time

- Equity holders

[Note that this article was written before Erin Koen’s proposal and, at the time of publishing, the Uniswap token fee switch has not been flipped.]

Notice how in theory, what was a simple step—fees accrue to token holders—is now a much more complicated combination of various options that all obstruct value accrual to token holders.

The Problem

Imagine if YouTube shareholders (also imagine YouTube is a standalone company, just for a moment) didn’t get any of the ad revenue generated from viewers on its platform. Instead this revenue went directly to creators p2p without YouTube collecting any platform fees. Rather than dividend paying shares, YouTube investors own a token that allows them to vote on the strategic direction of the platform. That would be extremely stupid.

“Oh but Ro, you’re missing the point—crypto is new and cool. You can’t financially model this stuff, so stop trying to, and have a bit of vision here” - an actual response I received.

Wrong. By and large, there is nothing new under the sun. Yes, the crypto community has done some innovative things—like bearer custody and the tying, clearing, and settlement of trades into a single transaction with DEXs—but when it comes to tokenomics, pre-crypto analogies are important. Crypto people like to think we’re operating in completely uncharted territory where basic financial principles are tossed out of the window. This should not be the case. Crypto is first and foremost a financial tool. Bitcoin was designed as a “peer to peer electronic cash system.” Value accrual is mission critical for any token’s success. While Bitcoin accrues value from monetary premium, application tokens need another angle. When exploring various tokenomic options, we can and should lean on decades of web2 history as a guide.

Delayed Monetization

In May 2009, DST and Yuri Milner made a $200M contrarian bet with a 1.96% stake into a then-nascent, unprofitable social media startup called Facebook. At this stage, many investors brushed off Zuck and Facebook as more of a public good than a proper business with profit potential. However, Yuri sensed Facebook’s ultimate ability to monetize. It didn't take long for vindication: Facebook posted its first profitable month in September 2009, just 4 months after DST cut that check.

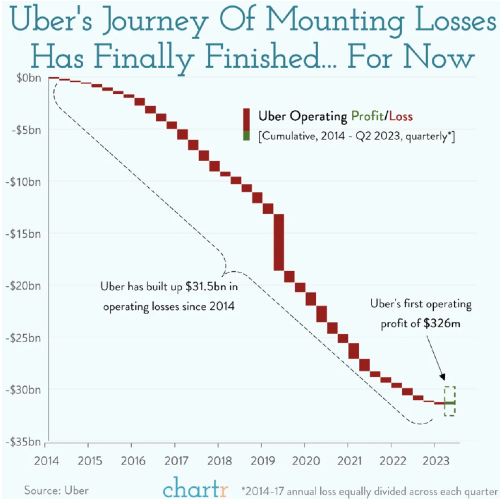

Uber is another example with a delayed monetization cycle, only with a significantly longer delay. For over a decade, Uber sacrificed profitability for market share. Only recently, after establishing their dominant foothold as the premier ride sharing app, have they shifted their focus to profitability.

As we see in the Facebook and Uber examples, delayed monetization can pay off. VCs tend to focus on market share over profits for growth-stage companies. With network-effect businesses that tend to be “winner takes all” (i.e., social media, ride sharing, or even a novel exchange structure like Uniswap), gaining market share at the expense of profits can make sense. On the other hand, the reverse—prioritizing earnings at an early stage—can affirm product-market fit. Maximizing a clearing price serves as evidence of solving a need and providing value to customers.

Uber and Uniswap share a similar initial playbook. Uber drivers effectively received p2p payments from riders, without Uber taking a meaningful cut, and LPs received 100% of the fees from takers, without UNI token holders taking any cut. This form of delayed monetization is a great way to incentivize two-sided marketplace growth; more money for drivers = more drivers joining the Uber network, and more fees for LPs means deeper liquidity on Uniswap.

There is, however, a sharp distinction between the right and the wrong way to delay stakeholder monetization. The right way is clearly communicating a viable plan to flip the switch down the line. The wrong way is hand waving token value accrual as some abstract dangling carrot that is perennially deprioritized. Many crypto projects do this the wrong way, and that is the big problem. Uniswap initially flipped the fee switch to equity holders instead of token holders, who were left holding a pure governance token. This clearly illustrates where Uniswap ranks (or, perhaps, ranked, given that we now know Uniswap may flip the switch the other way) token holders on their list of priorities.

Exceptions

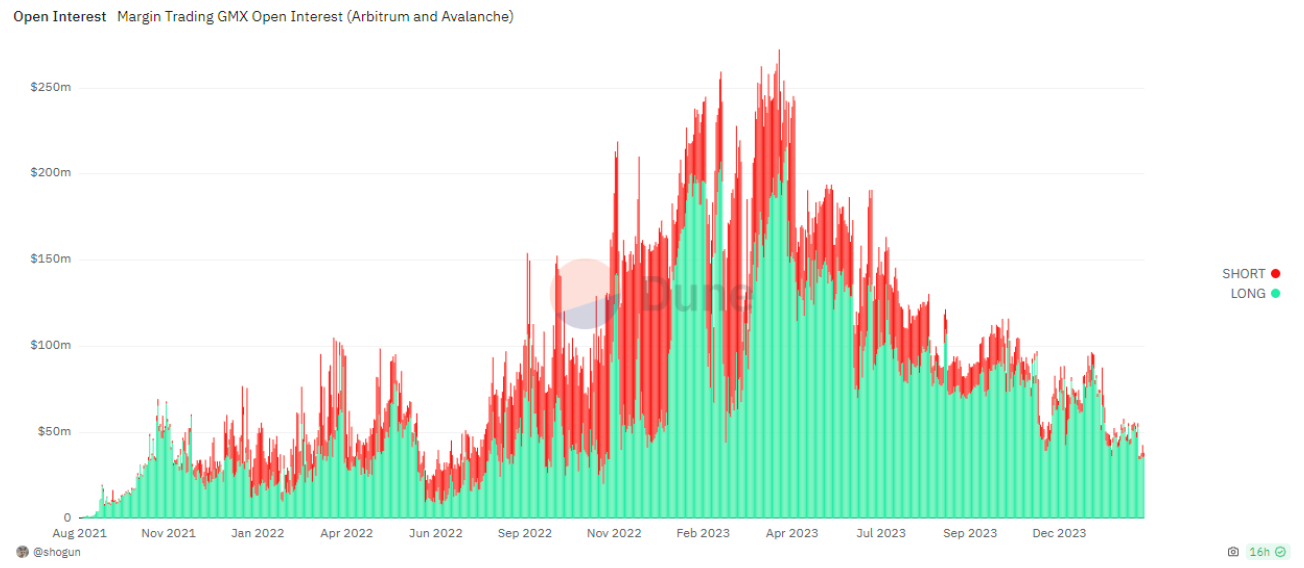

Not enough tokens accrue tangible value to their holders. One that immediately comes to mind, and a popular case study, is GMX. 30% of fees paid by traders on the platform accrue to GMX stakers (see https://gmx.io/). This is cool for a number of reasons:

- Staking GMX gives you direct exposure to fees generated by the platform

- As the platform grows (or shrinks), fees will grow (or shrink) along with it and the price of GMX today should reflect future platform expectations

- The traders are paying fees in WETH and the token holder payouts are in WETH. It’s simple: asset inflows and outflows are in-kind

When you look at the performance of GMX relative to ETH, it has exhibited significant outperformance when usage is growing. Similarly, when GMX fees drop due to dips in usage, it underperforms ETH. Funny how that works! This is evidence that transparent and straightforward tokenomics introduce a semblance of efficiency in crypto markets.

GMX/ETH Price (Purple Line) || Note: Left axis indicates market cap of GMX in units of ETH

GMX Aggregate Open Interest

Open interest is a proxy for fee generation and thus APY for staked GMX, Note that when fees trended upward, GMX’s price outperformed ETH, and when fees trend downward (as indicated by open interest since March 2023), its price underperformed ETH.

Regulation

The mental model I use to think about regulators’ role in marketplaces consists of three key elements: the market, the companies (protocols in crypto world), and the regulators. These are listed in order of speed. The market is at the forefront, representing the flow of funds of participants transferring risk and assets between one another. The companies enable the market to operate more efficiently by building venues, on- and off-ramps, brokerages, derivatives dealers, and similar necessary foundational blocks in a robust marketplace. The regulators trail the market and companies, ensuring everything operates in a fair, customer-protective manner.

Historically, the distance between the market, the companies, and the regulators has been fairly tight. That is true in the case of equities, as the marketplace where equities are traded is closely tied to the companies that build said marketplace (NYSE, CME, etc.) and the regulators are in the loop mostly every step of the way to stay on top of the entire operation. In this largely harmonious state, the different elements work together as a cohesive unit, contemporaneously.

Enter crypto, where the above tightly packaged unit is spread out into more distinct elements. The market enables peer-to-peer asset transfers and, more importantly, risk transfers via swaps in AMMs like Uniswap or similar DEXs to happen without a centralized company hosting the venue for trading. Trade, clearing, and settlement are all done in one atomic transaction, wallet to wallet. Companies that enable on- and off-ramps to crypto, like Coinbase, trail this marketplace and build services in support of what people wish to trade, in absence of clear regulations. Regulators watched the birth and evolution of this market from great distance, with little say in how it formed.

Regulators feel so behind and have proceeded to regulate with a “catch up” mentality that undermines capital formation and often fails to protect participants. In the US, this has led to regulation by enforcement and overt logical inconsistencies in SEC actions—as they say, “a cornered cat will make strange jumps.”

The profound irony here is that the SEC, whose objective is to protect investors from getting rugged on valueless tokens, is effectively making it prohibitively difficult for tokens to accrue value. If the SEC wanted to effectively protect investors, it would help construct a viable framework. The fact that the SEC has not tried to map any path along these lines is an egregious failure of responsibility in my view.

Indeed, this failure extends beyond token value accrual. It is mind blowing that two consenting adults, one in America with a complete understanding of financial derivatives, and one in, say Singapore, running an off-shore derivatives exchange, have zero legally viable path to shake hands and do business together, yet this is the world we live in today. Americans are also prevented from claiming literal free money in airdrops. Meanwhile, they are fully approved to blow their savings in regressive tax schemes, such as the lottery. Irony oozes from the reality of this bifurcation.

The Solution

So, how should we structure tokens today? Although there is no silver bullet, one-size-fits-all answer, here are a few available options with varying viability (by no means an exhaustive list):

- Offshore: build your project completely offshore and ensure not a single American user touches the platform

- Register: try to register your token with the SEC and then accrue value to it

- Give up: wait for further regulatory clarity, go back to pushing carts at Walmart in the meantime

- Full send: send it without geoblocking and just accrue value to the token out of the gate

- Backdoor fees: do something creative with appchains like dYdX where value accrues to tokens via PoS staking, backdooring fee distribution into consensus mechanism

- Fee switch: slap a “governance” label on your token and flick on a “fee-switch” later via governance vote

Of all the options, a combination of backdoor fees and fee switch likely balances legal risk and value accrual best without completely throwing in the towel and giving up.

Ethereum is effectively backdoor fees with the accrual occurring at the L1 level rather than a specific appchain—people pay fees to do things and a slice of those fees are passed back to ETH holders via PoS consensus and the EIP-1559 burning mechanism. Translating that concept to app tokens is key to climbing out of the governance rut.

One issue with the backdoor fees model is that it’s seeming incompatibility with many types of protocols. Something that is a more contained ecosystem, for example a DEX like DYDX, can viably have an appchain. However, for applications such as liquid staking derivatives, having an app-chain might seem like it makes less sense.

For those types of applications, the fee switch is still suboptimal. The JTO tokenomics start with pure governance but in theory a fee switch can be enacted via governance vote. The main issue with this is that a foundation sitting on top of the governance proposals intentionally could delay or super veto the switch in one way or another. I’d argue that you should do whatever you can to jam backdoor fees into your protocol, even if that means launching an otherwise unnecessary appchain for your liquid staked derivative.

Full send presents the most legal risk and is ill-advised, giving up is quitting (perhaps what the SEC wishes), registering is by all means practically impossible, and offshore is unfortunately here to stay until we see changes at the SEC, including if you choose either of the last two options.

The options above are not perfect by any means and the right one for your project will depend on, well, your project. The ultimate solution needs to be an SEC with a more modern approach of regulating digital assets that truly protects investors and allows tokens to do what they do best. Though less pragmatic, I say this because it’s the only real long-term solution and I’m optimistic that over a number of years it’s plausible as governments realize investor interests and protections are both optimized through tokenization.

Conclusion

Pure governance tokens fly in the face of the stakeholder benefits at the core of crypto’s utility. They exist because founders are afraid of regulators and or as an excuse to exclude token holders from their economics. A new and improved SEC will take time, but rather than cowering in fear behind a pseudo-protective curtain of valueless governance tokens, founders should think of creative ways to build value accrual into them. Of all the options presented here, bundling fee distributions within consensus, particularly in the context of appchains, seems to be the most viable, legal risk-adjusted approach available today. If that sounds like it doesn’t work for your project, figure out a way to make it work. In any case, this backdoor approach is still likely to geoblock Americans, so if you are in the US, Walmart is always hiring, but at least the tokens are accruing some value.

Thanks for reading.

The information herein is for general information purposes only and does not, and is not intended to, constitute investment advice and should not be used in the evaluation of any investment decision. Such information should not be relied upon for accounting, legal, tax, business, investment, or other relevant advice. You should consult your own advisers, including your own counsel, for accounting, legal, tax, business, investment, or other relevant advice, including with respect to anything discussed herein.

This post reflects the current opinions of the author(s) and is not made on behalf of Hack VC or its affiliates, including any funds managed by Hack VC, and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of Hack VC, its affiliates, including its general partner affiliates, or any other individuals associated with Hack VC. Certain information contained herein has been obtained from published sources and/or prepared by third parties and in certain cases has not been updated through the date hereof. While such sources are believed to be reliable, neither Hack VC, its affiliates, including its general partner affiliates, or any other individuals associated with Hack VC are making representations as to their accuracy or completeness, and they should not be relied on as such or be the basis for an accounting, legal, tax, business, investment, or other decision. The information herein does not purport to be complete and is subject to change and Hack VC does not have any obligation to update such information or make any notification if such information becomes inaccurate.

Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results. Any forward-looking statements made herein are based on certain assumptions and analyses made by the author in light of his experience and perception of historical trends, current conditions, and expected future developments, as well as other factors he believes are appropriate under the circumstances. Such statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to certain risks, uncertainties, and assumptions that are difficult to predict.